|

Death Gods, Smiling Faces and Colossal Heads: Archaeology of the Mexican Gulf Lowlands by Richard Diehl |

|

| |

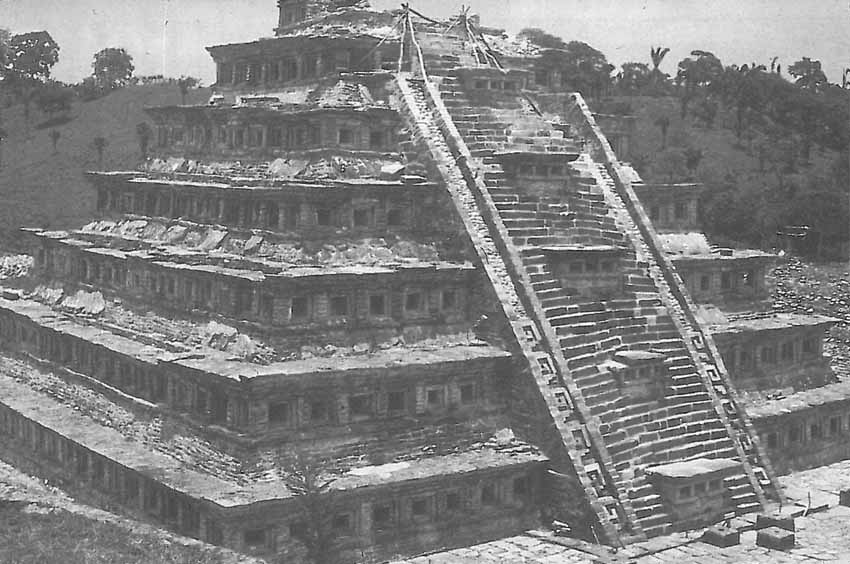

The Late Classic (A.D. 600-900) Gulf Coast lowland populations reasserted themselves culturally and politically during the Late Classic period. It is not clear whether this resurgence provoked a break in the contacts with Teotihuacan or simply reflected it. In any case the geographical focus of power and innovation shifted northwestward to El Tajin, in the densely forested hilly terrain along a tributary of the Rio Tecolutla. El Tajin was occupied between A.D. 100-1100, but its florescence occurred during the tenth and eleventh centuries, at the very end of the Late Classic or what some call the Epi-Classic. At this time it dominated much of the surrounding area and maintained commercial and perhaps political relationships with centers in Yucatan and the Pacific Coast lowlands from Chiapas to El Salvador. El Tajin contains many large buildings erected on the artificially terraced ridge sides ascending from the small stream that drains the area. They include scores of temples, eleven ballcourts, a palace complex, and numerous other public buildings covering 2.5 square kilometers. El Tajin is famous for its distinctive art style reflected in architecture, sculpture, and portable carved stone objects; the large number of ballcourts; and its preoccupation with death and the underworld. In the realm of architecture El Tajin is noted for the use of recessed niches, stepped-fret panels, and outward-projecting, "flying" cornices. The Pyramid of the Niches is the best-known exemplar of this style (Fig. 4.6). This temple base was constructed in seven levels, each with a sloping talud and vertical tablero. Three hundred sixty-five recessed niches adorn the four sides. The correspondence between the number of niches and the number of days in the solar year is surely not a coincidence, especially since Mesoamericans utilized a 365-day solar calendar divided into eighteen months of twenty days each with five additional days added to the end of the cycle. Most of El Tajin's buildings were painted vibrant colors, the Pyramid of the Niches was red while the niches themselves were black. Other buildings were painted a very distinctive blue, of which substantial traces remain even today.

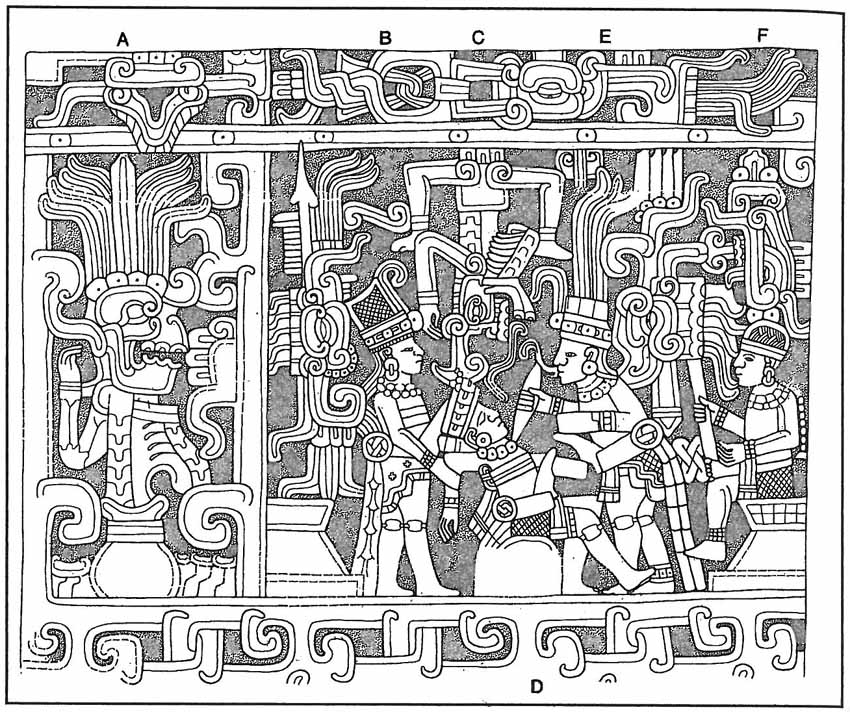

El Tajin is famous for its stone sculptures depicting narrative scenes, especially the finely carved round stone pillars that supported the roof of the Building of the Columns and the panels placed in the playing-field walls of the North and South Ballcourts. According to S. J. K. Wilkerson, the scenes on the pillars depict myths or historical accounts (be they true history or not) of the exploits of a ruler named 13 Rabbit. The one scene which is complete enough to reconstructed shows this tenth-century ruler observing the sacrifice of captured enemies. The six panels on the walls of the South Ballcourt exemplify precolumbian narrative art at its finest (Fig. 4.7). They portray sequential stages in a ball game and sacrifice ritual. The account begins with (1) ceremonial preparation in which the protagonist dresses, followed by (2) music and dance prior to a ball game, (3) the actual playing of the ball game, (4) the end of the game with sacrifice of one of the players, (5) the descent of sacrificial victim into the underworld to obtain pulque, an intoxicating fermented cactus sap with sacred qualities. In the last scene (6) a god refills the pulque container by perforating his penis and allowing the blood to enter the pulque vat, thus completing the cycle.

The Mesoamerican ball game was a ritual rather than a sport in the modern sense. It played a crucial role in rituals conducted when classic Maya rulers ascended to the throne, and the Aztecs played it in order to foretell the future. It may have functioned similarly at El Tajin, but the large number of courts at the site suggests that ball game rituals were celebrated much more frequently there than elsewhere. The precise relationship among the ball game, human sacrifice, death, and the skeletal figures so common at El Tajin and other Gulf Coast lowland sites is not clear. Some scholars believe that the death "cult" personified by Mictlantecuhtli and his consort, Mictlancihuatl, the Nahuatl Death God and Goddess, originated on the Gulf Coast. Whether that is true or not, there is good evidence that the Olmecs played the ball game; rubber balls have been recovered at El Manati, a mound complex at San Lorenzo has been identified as a ballcourt, and Olmec clay figurines depict men dressed in protective garb while holding balls in their hands. Further evidence for the importance of the ball game in Late Classic lowland Gulf Coast culture can be seen in portable stone sculptures called yokes, hachas, and palmas. Yokes are U- or oval-shaped stone belts. Some are open on one end, others are closed; many have plain surfaces, while a few have intricate low-relief carving on their surfaces. Stone yokes seem to be replicas of the wood or cloth protective belts worn by ballplayers during the game (Fig. 4.8). Some yokes are large enough to fit slender adults, but their weight suggests that they were worn in ceremonies rather than actual play. Hachas are thin stone anthropomorphic or zoomorphic three-dimensional heads while palmas are fanlike devices. Stone sculptures occasionally show men wearing yokes with hachas attached to the front and palmas placed on the back.

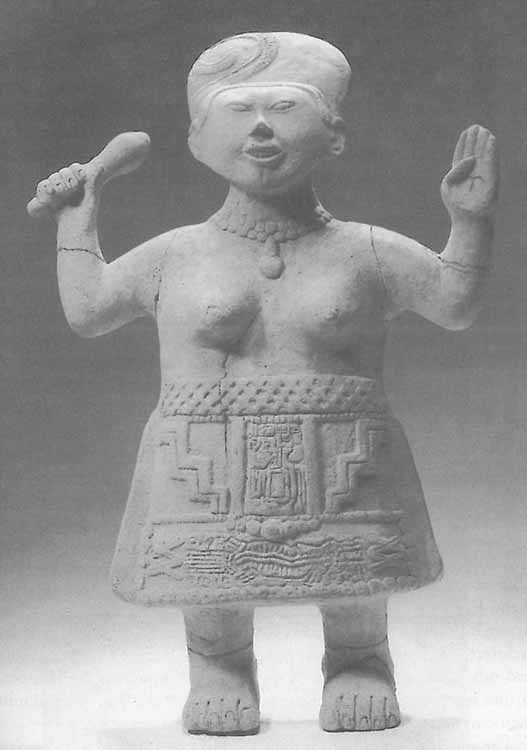

El Tajin must have been the capital of a major regional state encompassing much of northern Veracruz and adjacent areas. Remnants of drained fields in swampy terrain, evidence of intensive agriculture dating to the Late Classic, suggest that populations were sufficiently dense to permit and even require substantial investments of time and energy in agriculture. Commercial "cash crop" cultivation of cacao or cotton also seems likely. El Tajin fell on bad times during the late tenth or perhaps the eleventh century. The nature of the difficulties is not known, but the city was ultimately burned and abandoned. Unfortunately, the processes that led to its decline are as unclear as the date of its abandonment. Although the area continued to be occupied, no immediate successor to El Tajin has been identified. Late Classic sites are abundant in central and southern Veracruz, but the information available on them is very confused. The hollow figurine tradition reached its climax with the renowned "smiling face" figurines, hollow clay whistles depicting standing boys or girls with outstretched arms, grotesquely flattened heads, pillbox headdresses, and idiotic smiles (Fig. 4.9). Various explanations have been offered for the bizarre facial expressions, but the most likely is that they portray intoxicated or drugged sacrificial victims. Smiling face figurines are only one of many Late Classic figurine types placed in caches and burial offerings in central southern Veracruz. Other small clay sculptures depict people sitting on swings, animals mounted on wheels, seated skeletonized figures with grinning countenances and cross-legged old men with braziers on their heads, perhaps a variant Huehueteotl, the Old Fire God of highland central Mexico.

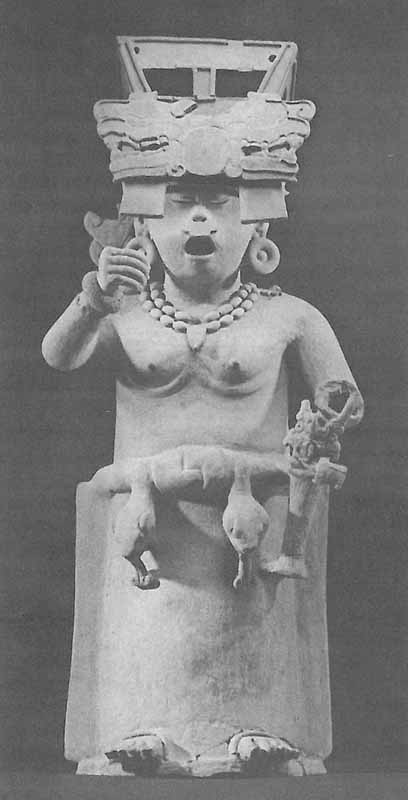

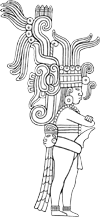

The Late Classic potters in central Veracruz also produced spectacular life-size ceramic sculptures unparalleled in the rest of Mesoamerica. The most remarkable of these come from El Zapotal, near Cerro de las Mesas. Here Mexican archaeologists uncovered a sanctuary containing a seated life-size skeletal figure made of unaired but painted clay. Elsewhere in the same structure they found lines of large hollow sculptures of Cihuateteotls, women wearing skirts held in place by serpent belts (Fig. 4.10).

|

|

|

Text links to all pages at this site are available at the FAMSI INDEX |

||